Dancing Heroes

Dancing Heroes Glamour - Marzo 2018

di Nina Verdelli | ph. Luca Babini

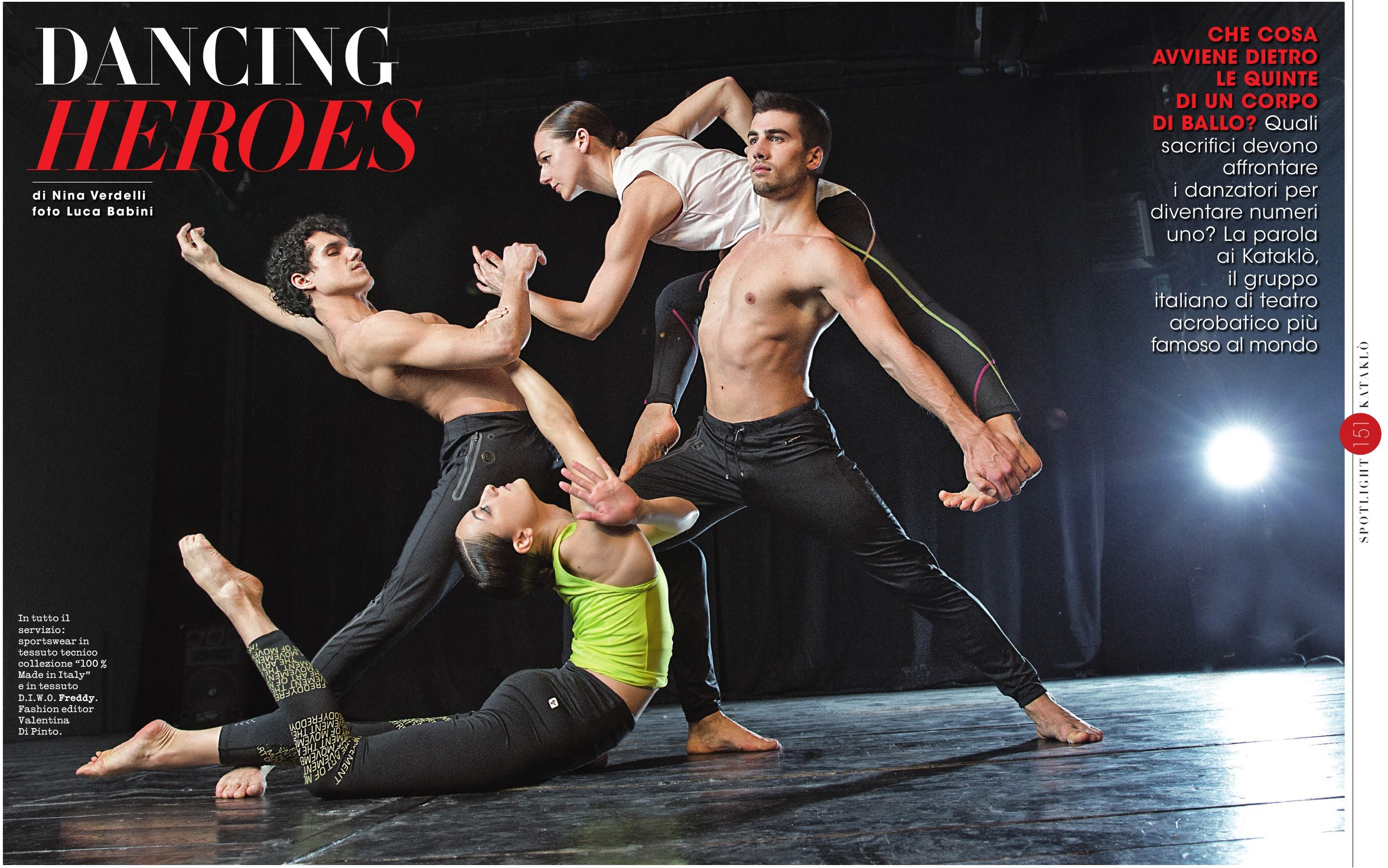

What happens behind the scenes of a dance troupe? What sacrifices do dancers face for one? The word from Kataklò, the world’s most famous Italian acrobatic theater group.

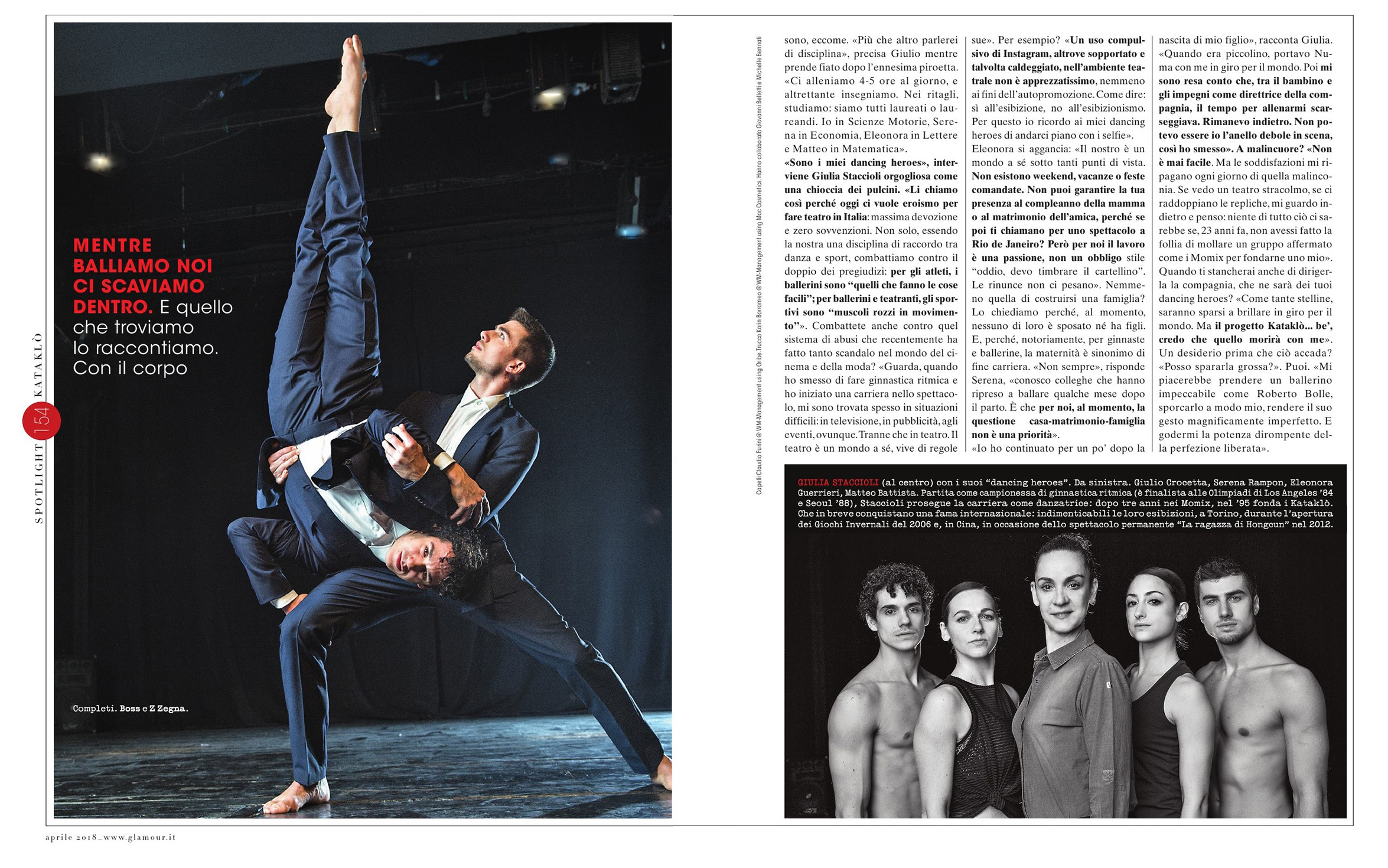

There are no perfect dancers. The important thing is that the dancers are eager to be. Katakló are. As we dance we dig in. And what we find we tell with the body.

Stop. I can’t focus-I can’t tell where one begins and the other ends, smiles photographer Luca Babini at the four dancers entwined with each other like tree roots. The legs

of Serena’s blends with Matthew’s, Eleanor’s arm ends where Julius’s begins, forming a single branch pointing toward the sky. Or rather, toward the ceiling of the Avirex Theater in Milan.

A closed-door show is being staged on the stage: before they fill squares all over the peninsula this summer with their Summer Eureka show, Kataklò are performing today exclusively for Glamour.

The world’s most famous Italian physical theater group needs only a glance to unite the four marble bodies into one dynamic and harmonious statue. In part, the movements are improvised; in part, they are borrowed from the vast repertoire of the company led by former gymnast Giulia Staccioli who, after two Olympics and three years as a performer with the American acrobatic dance group Momix, founded her own project in 1995: Kataklò, precisely. She too with us today, sitting in the darkness of the stands, watching and following “her boys” with imperceptible stiffening of the neck. Only from time to time does he stand up and, like a careful but unobtrusive conductor, impart a suggestion, “Serena, break the lines.” Which, in technical language, means “bend your legs.” On the other hand, Staccioli explains, “Ours is an imperfect dance.” Imperfect because except for a few cases in the world-Rudolf Nureyev, Michail Baryînikov, Roberto Bolle-there are no perfect dancers. “The important thing,” Giulia continues, “is that the dancers are eager to be. And mine are.”

But also imperfect because his choreography is born out of the athletic gesture, adulterating it. The name Kataklò itself says so; in ancient Greek, it means “I dance by bending and twisting.” Translated: all performers have an athletic background behind them, whose power and elasticity they retain, but whose rigidity of movement and precision imposed by predetermined codes they abandon.

“For me it was a liberation,” interjects Matteo Battista, 24, from Milan, who of the articircenses corrected the posture. “When you start studying dance, you understand that movement is not an end in itself: it is a means of communication, a way to tell a story. Your story. As I dance, I dig into myself, and what I find I tell, with my body. Almost likea psychotherapy session.” Agree former gymnast Giulio Crocetta, 27, from Vicenza, and Serena Rampon, 37, from Padua, who has a background in rhythmic gymnastics. Eleonora Guerrieri, 26, from Milan, is the only one with a dance school behind her. In the pause between shots, clenched in her bun and “comfortably” sitting in the split, she says, “Unlike my colleagues, I did not have to give up anything from my training as a dancer. On the contrary,I had to build acrobatic skills. Let me just tell you that I spent four months attached to the rings before I was able to perform a single pull with my arms.”

The statement is somewhat reminiscent of Lieutenant Seeger (a.k.a. Lisa Eilbacher) from Officer and Gentleman: the only woman among so many aspiring pilots, she spends days and nights crying and sweating, insulting and punishing, before she manages to climb a rope to climb over a wall. The same dedication hovers among the Kataklos here, but the atmosphere is softer: no Royal Ballet School snobbery, no mistreatment or unrestrained competition Black Swan style. Eleonora continues: “The ruthlessness of ballet is one of the reasons why I did not attempt a career in that environment. There you have to scramble to be in the front row, there is obsessive weight control, the psychological pressures are enormous. With us, on the other hand, the influence of sports is very strong: like athletes we can eat more because we burn more and, as in team play, the performances enhance collaboration.” “That’s also why, when we’re on tour, we seem a bit like one big family,” echoes Serena, who joined her colleague in a split, as if it were the most natural pose in the world. In front of the photographer’s lens now are just Julius and Matthew performing backflips as easily as mere mortals climb over a puddle.

These equations, “splitting equals comfort” and “screwing equals triviality,” are enough to understand that, beyond understatements, the sacrifices are there, and how. “More like discipline,” Julius points out as he catches his breath after yet another pirouette. “We train 4-5 hours a day, and as many we teach. In the scraps, we study: we are all graduates or undergraduates. Me in Exercise Science, Serena in Economics, Eleanor in Humanities and Matthew in Mathematics.”

“They are my dancing heroes,” interjects Giulia Staccioli as proud as a hen of chicks. “I call them that because it takes heroism to do theater in Italy today: maximum devotion and zero subsidies. Not only that, since ours is a bridging discipline between dance and sports, we are fighting against double the prejudices: for athletes, dancers are ‘those who do the easy stuff’; for dancers and thespians, sportsmen are ‘rough muscles in motion.'” Do you also fight against the system of abuse that has recently been so scandalous in the world of film and fashion? “Look, when I stopped doing rhythmic gymnastics and started a career in entertainment, I often found myself in difficult situations: on television, in commercials, at events, everywhere. Except in theater. Theater is a world of its own, it lives by its own rules.” For example? “Compulsive use of Instagram, elsewhere endured and sometimes advocated, in the theatrical environment is not appreciated, not even the purposes of self-promotion. As in: yes to performance, no to exhibitionism. That’s why I remind my dancing heroes to go easy on the selfie.”

Eleanor hooks up, “Ours is a world of its own in so many ways. There are no weekends, vacations or holidays. You can’t guarantee your presence at your mom’s birthday or your friend’s wedding, because what if they call you for a show in Rio de Janeiro? For us, though, work is a passion, not an obligation in the style of “oh my God, I have to punch a clock.” Renunciations don’t weigh us down.” Not even that of building a family? We ask because, at present, none of them are married or have children.

And, because, famously, for gymnasts and dancers, motherhood is synonymous with the end of their careers. “Not always,” Serena replies, “I know colleagues who started dancing again a few months after giving birth. It’s just that for us, at the moment, the home-marriage-family issue is not a priority.”

“I continued it for a while after my son was born,” says Julia. “When he was little, I used to take Numa with me around the world. Then I realized that between the baby and my commitments as company director, time for training was scarce. I was falling behind. I couldn’t be the weak link on stage, so I quit.” Reluctantly? “It is never easy. But the satisfactions repay me every day for that melancholy. If I see a packed theater, if we double our performances, I look back and think, none of this would be there if, 23 years ago, I hadn’t done the folly of quitting an established group like Momix to start my own.”

When you also get tired of running the company, what will happen to your dancing heroes? “Like so many little stars, they will be scattered to shine around the world. But the Katakló project … well, I think that one will die with me.” A wish before that happens? “Can I shoot it big?” You can. “I would like to take a flawless dancer like Roberto Bolle, soil him in my own way, make his gesture magnificently imperfect. And enjoy the disruptive power of perfection liberated.”

Source : https://moda.mam-e.it/missoni/

Director: Tommaso Ottomano

Performers: Eleonora Guerrieri Matteo Battista Stefano Ruffato Carolina Cruciani Sara Palumbo Simone Paris